The truth is, I’m not a gamer. I do not have the depth of experience playing games like true gamers do. Yet, over the past few years, I’ve discovered a real love for designing games with my Kindergartners! Making games with young children is a process rich with imagination, challenges, collaboration, connections, and joy. This blog is a personal reflection on my growth as a game designer. It’s only been two years, and I’m excited that I’ve come such a long way!

What games do you play?

At home, I play some games with my family. We enjoy playing Labyrinth, Sleeping Queens, Rat-a-Tat Cat, Sorry, Scrabble, Jenga, Pictionary, and various card games like Crazy 8s, and Go Fish.

How did you decide to make games with kids in the first place?

Two years ago, while getting to know my Kindergartners, I learned a big lesson. There is a massive difference between playing games and making games with children. I had introduced many types of games to my students - mathematical, literacy-based, just-for-fun - yet, no matter the type of game we played, my feisty and strong-willed Kindergartners wanted to triumph over each other. Friendships suffered and competition was at an uncomfortable high. My students needed a reason to come together, to share ideas, and to grow as a community of problem-solvers. Game-design was the answer.

One day, I found inspiration from a student who brought in a beautiful homemade painted display of a jungle swamp to share. As a class, we discussed how much fun it would be to turn his display into a 3D game. Soon after, Chutes, Ladders, Bridges and Bananas was born! Our first game brought my students together. Everyone contributed and everyone’s ideas mattered. Most importantly, it was a lot of fun! The success of this simple game led me to seek more opportunities for my students to design games.

What are the other inspirations behind your games?

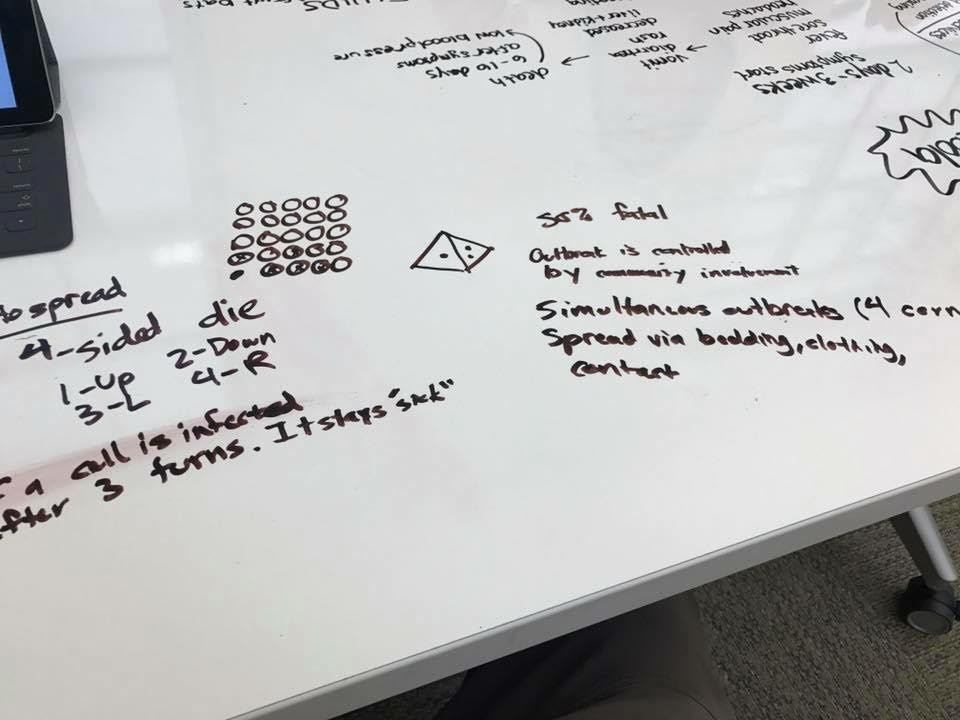

After finding inspiration from art, the games I have made with my students over the past two years have been inspired by creative writing, dice, relative size, paleontology, and mapping. Games are also inspired by my hope for students to develop communication literacy tools - listening, sharing, offering and receiving feedback, taking on the perspective of others, and exhibiting their work. In addition, I am interested in connecting my students’ ideas with their growth as mathematicians.

My main inspiration to continue making games with kids is that, in all of my many years as an educator, I have never found a better fit for developing growth mindset than through game-design. There are countless opportunities to make mistakes, reiterate, solve problems, and find comfort in the process, wherever you are.

What were the challenges you had early on and how did you address them?

Initially I asked lots of questions and relied on the advice from experienced game designers. After modding two games, I felt quite unsure I would ever be able to create a game from scratch. I struggled with focusing on specific learning goals for my students...there were so many! Did I want to focus on temporal skills like taking turns? Spatial awareness? Mathematical concepts? I needed to simplify, and I tended to make things too complicated. After designing a super complex game with my students about relative size, I tried addressing my concern in the next game we made. It was still complicated and long, but more organized and much more fun! In designing our most recent game, I knew I wanted my students to use a compass and I wanted them to have opportunities to make strategic choices. Their choices guided the rest of the design! Ultimately, I want the games we make to be just as fun as the learning my students and I do along the way!

What advice would you give someone on their first try?

Start by making observations of your students! Ask yourself questions!

How do they play games?

What types of games do they enjoy?

What skills are they developing?

What do they care about?

Do they seem more interested in collaborative or competitive games?

How can you merge their passions with your understanding of their growth as mathematicians, readers and writers

Once you have a game idea, you might treat it like writers do when beginning a story. My students recently created a mapping game and asked the following questions.

Where might our game take place?

Who would the characters be?

What will they need to do?

How will they do it?

What types of problems might they need to solve?

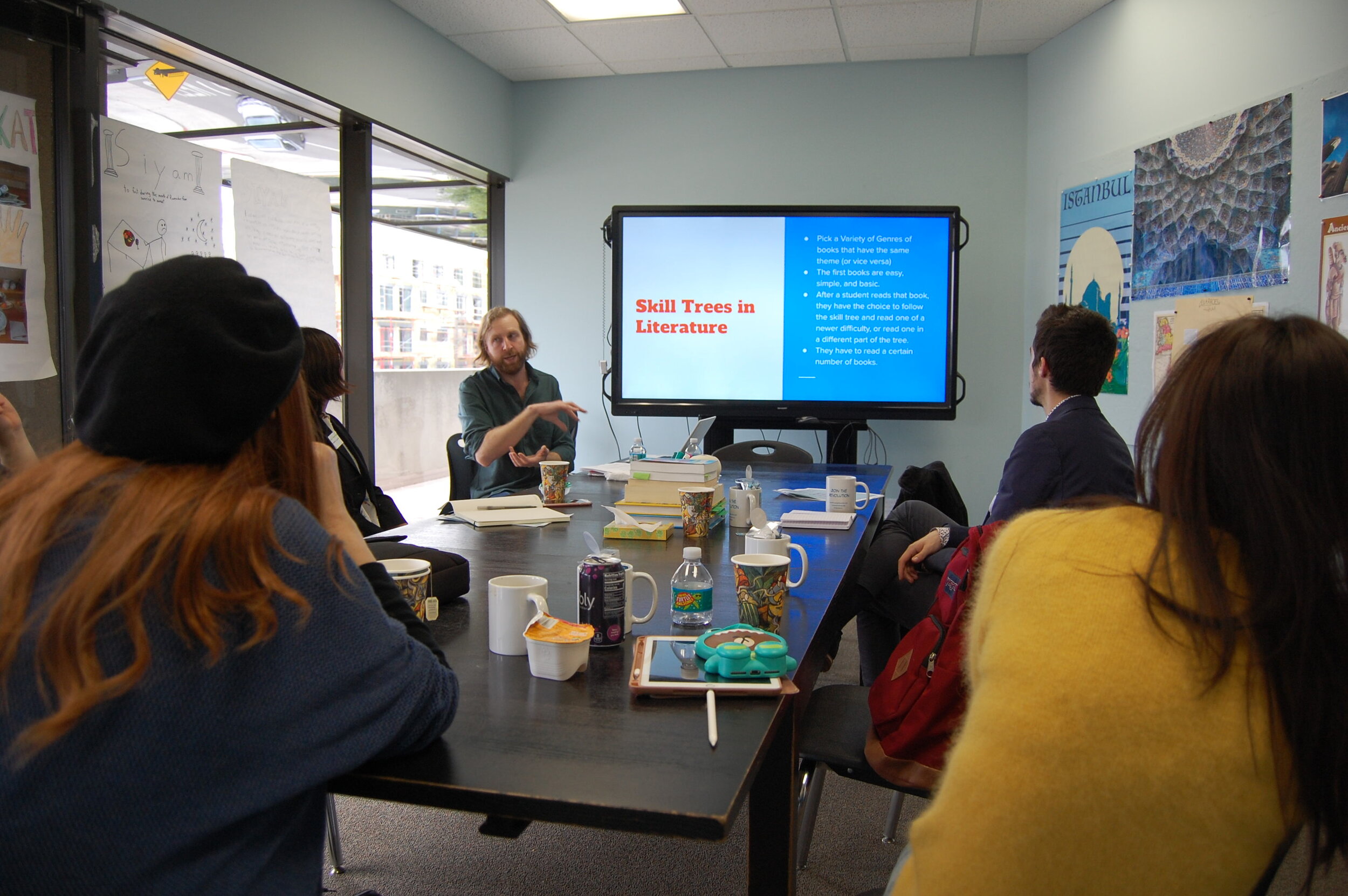

Sleep on it before making decisions. When I extend the brainstorm phase longer than I am comfortable (and way longer than my students are comfortable), amazing things began to happen. A lot of excitement builds as children anticipate the synthesis of their ideas. Creative juices flow and children think critically about what would make the best game!

When designing game boards, you can expect to make many iterations to your initial idea. My students often playtest different size game boards with fifth graders and make decisions after collecting feedback.

Process is important! It’s not easy to slow down 5 and 6 year olds with boundless energy. Yet it’s completely worth all of the effort. My students’ awareness of their game-design process is the ultimate game-design goal. They need many chances to reflect on where they are in the game-making process and plan for next steps, if they are going to truly own it.

What do you enjoy about making games with kids?

I enjoy letting kids choose and supporting them to discover all of their learning that goes into making a game. When Kindergartners consider each others’ ideas, make decisions, and laugh when they make mistakes, I feel proud. I also enjoy learning how to use the 3D printer to create game pieces, dice, and spinners. This involves lots of problem-solving and iterations - valuable lessons for my students to learn alongside me. Synthesizing my students’ art into a game board or game pieces is another element that I enjoy. Most exciting is watching my students share their games with parents and other students at school!

What are the most notable learning outcomes from making games?

Game design is an excellent way for me to let go of my plans and go with the flow...something I enjoy quite a bit! I see myself as an “out-loud wonderer,” asking open questions that help my students make their own choices. I always observe that the games we develop bring out much deeper learning than the content they originally were meant to explore. Two years ago, I did not know anything about 3D printing and now, a notable learning outcome for me is that I can design with my students and print anything they need...including a spinner that fit into the game board!

For my Kindergartners, the most notable learning outcome is the discovery that they can successfully collaborate as a class through mistakes and challenges. Through game-design, students get relevant experience developing a growth mindset. Students practice thinking critically while playtesting, developing solutions, and reiterating. They can merge their imagination with research and bring it to life in a game! Communications literacy skills grow as students engage in meaningful discussions or debates. They have opportunities to illustrate, write rules, and create labels. While learning about taking turns (temporal awareness) and moving on the game board (spatial awareness), students tune their mathematical reasoning. In game-design, my Kindergartners explore probability, moving on a numberline, skip-counting, visualizing numbers, measuring, deductive reasoning, and making strategic choices.

What has been the most difficult thing to change in your process?

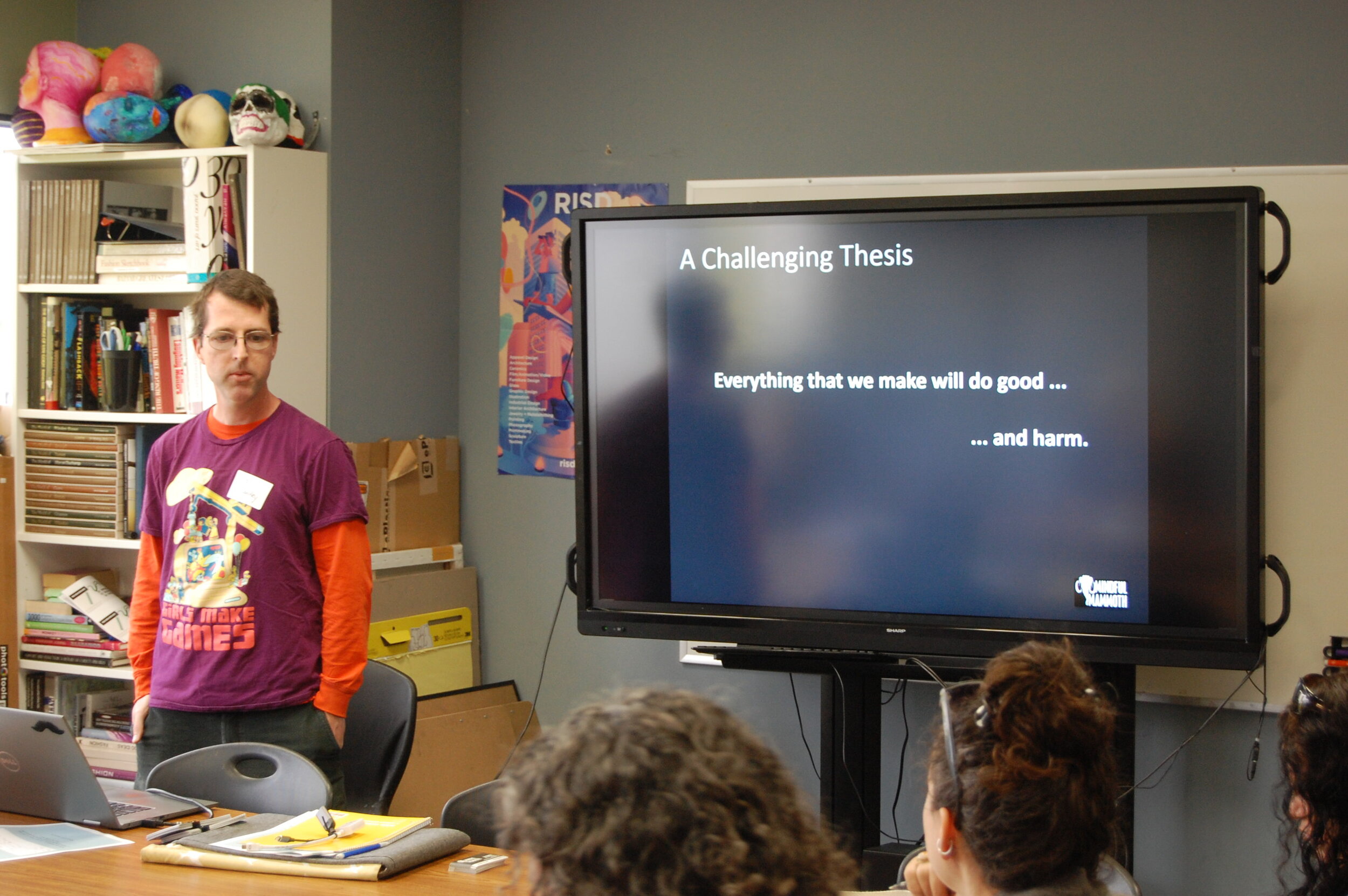

I enjoy working with experts and appreciate the way they have given me the freedom to grow as a game-designer. Since I have less experience as a gamer than most game-designers, the most difficult thing for me to change is developing an intrinsic understanding of game mechanics.

What are your next steps as you continue to grow as a game designer?

I look forward to continuing to dream big with my students, while focusing on to keep our games simple. It’s a tricky balance - managing the endless creativity that comes from Kindergartners with the reality of the game-design process. I’m also looking forward to deepening my knowledge of the tools I can use to create 3D printed game pieces and, of course, to grow as a game designer, I need to play more games...it’s fun research!